New from NPR 老鼠也有高尚情操!

這年頭人心險惡,看來還不如跟老鼠做朋友!

下載聲音檔請點我

Cagebreak!

Heard on Morning Edition

December 9, 2011 - LINDA WERTHEIMER, HOST:

Calling someone a rat means you think they're a scoundrel, the kind of person who would abandon others in their time of need在需要的時候. A new study shows actual rats are not like that. NPR's Nell Greenfieldboyce reports rats will actually lend a helping paw伸出援手(原本是做lend a helping hand,這邊的paw是動物的手掌) to a cage mate in distress.在危難的時候

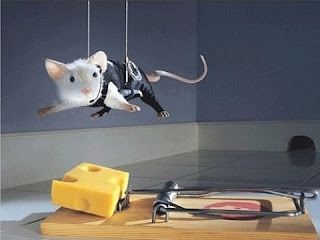

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE, BYLINE: Pretend you're a rat. For a couple of weeks, you've lived with a cage mate. You've gotten to know each other. One day, your cage mate disappears. A human picks you up and puts you in a plastic box. There, before you, is your cage mate – trapped身陷 in a narrow, plastic tube, clearly unhappy, maybe even making ultrasonic distress calls超音波求救訊號 that you can hear because remember, you are a rat.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: What would you do? Peggy Mason is a neurobiologist at the University of Chicago. She and her colleagues recently put rats in this situation. And, she says, it's as if the free rat immediately sizes things up and takes action馬上評估狀況並且採取行動. The rat will go to the tube where its pal夥伴 is imprisoned, stand on the tube, bite it, paw at it用手掌去打管子.

DR. PEGGY MASON: So the free rat wants the trapped rat to be free.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: The free rat tries everything to get its friend out. Mason says the trap has little air holes in it.

MASON: And if the trapped rat has a tail poking out露出來, the free rat will actually grab that tail and kind of pull on it.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: Eventually, the free rat will accidentally trigger促使 a door that opens, releasing its buddy.

The researchers repeated this experiment many times. The animals quickly learned to open the door on purpose. But they only did so for a pal, not when the trap was empty or contained a toy rat. And they did this even when opening the door released their pal into a separate cage. So it wasn't just that the free rat wanted a playmate. They seemed to just want to help.

The results are reported in the journal Science. Mason says she wanted to find some way of understanding what this helping action meant to the rats.

MASON: What is this worth to you, to open the door for a trapped cage mate? And obviously, we can't ask that question verbally. So we wanted to ask it in terms that a rat can communicate to us.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: Rats really care about food, and they love chocolate. So Mason's team tried putting two traps inside the plastic box: inside one, yummy chocolate chips; inside the other, the distressed friend. What they found is that the free rats would quickly open both traps, and in no particular order沒有特定順序.

MASON: So what that tells us is that liberating a trapped cage mate has a value that is on a par with一視同仁的/勢均力敵的(兩者的處理態度相同) chocolate.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: What's more, even though the free rats could've just gobbled狼吞虎嚥 all the chocolate and then released their friend, they instead chose to share the candy with their fellow rat.

DR. JEFFREY MOGIL: You know, it’s one thing to free the trapped rat that might be making alarm calls. It's quite another thing to share the chocolate chips. I was actually really, really surprised by that point.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: Jeffrey Mogil, of McGill University in Montréal加拿大蒙特婁大學(位於東南部魁北克省Quebec), has previously shown how mice seem to pick up on the distress of their cage mates. He says this new study is a dramatic confirmation透過非常極端或是戲劇化的方式去證明一相理論; that it's not just primates靈長類動物 who can feel a friend's pain and try to help.

MOGIL: It's always been strange to me that people think that these social abilities that humans have are human-specific只有人類才有的/人類專屬的, as if they'd just arrived out of nowhere with no evolutionary antecedents.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: He says it looks like the roots of empathy and altruism同理心與利他主義 go way back, and the rat experiment gives scientists a new tool for studying the biology of this behavior in the lab.

Nell Greenfieldboyce, NPR News.

留言

張貼留言